NASA has canceled a $1.5 billion project that was likely going to cost about $1 billion more to get to the launch pad. The mission was intended to test robotic satellite servicing technologies in orbit, but it was overbudget and behind schedule.

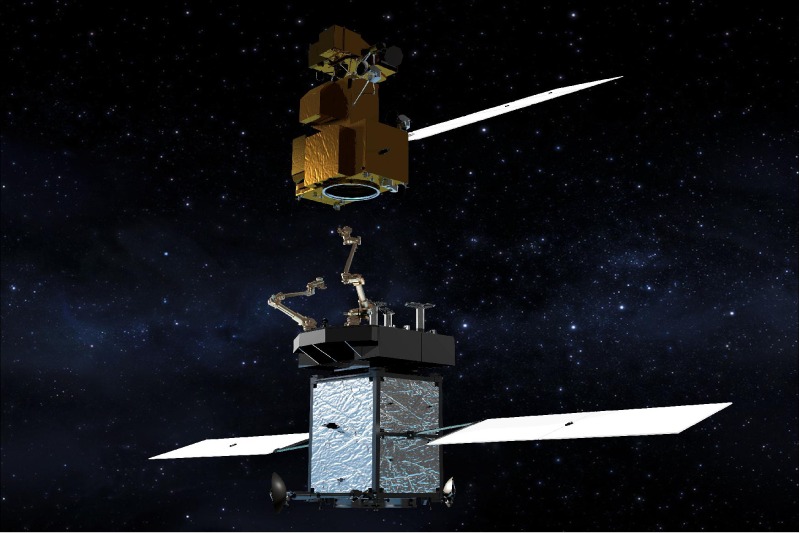

In addition to attempting to refuel an aging Landsat satellite in orbit, the On-orbit Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing 1 mission, or OSAM-1, would have demonstrated how a robotic arm could build an antenna in space. Although the OSAM-1 mission’s spacecraft is half constructed, NASA declared on Friday that the project has been canceled “following an in-depth, independent project review.”

The space agency announced that OSAM-1 would not be proceeding due to “continuing technical, cost, and schedule challenges.”

Mission Creep

The cost of the mission has increased dramatically since NASA began work on it in 2016. Only the refueling demonstration was part of the mission’s initial plan, but in 2020, officials added the in-orbit assembly goal. The Space Infrastructure Dexterous Robot (SPIDER), which is effectively a 16-foot-long (5-meter) robotic arm, has to be added in order to combine seven structural components into a single Ka-band communications antenna.

With the inclusion of SPIDER, the mission would have three robotic arms at launch, including two appendages required to grasp onto the Landsat 7 satellite in orbit in order to perform the refill. The operation was renamed OSAM-1 from Restore-L due to this scope adjustment.

The mission’s delays and cost overruns were detailed in a report released by NASA’s Inspector General last year. Congress has been asked to approve $808 million by the space agency for Restore-L and OSAM-1 since 2016. In response, lawmakers gave NASA around $1.5 billion to fund the mission’s development—nearly twice as much as the agency had requested.

Congress has consistently supported Restore-L and later OSAM-1. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland oversaw the mission. Former Maryland senator Barbara Mikulski (D) was a major supporter of Goddard-based NASA programs, such as the James Webb Space Telescope. She was the Senate Appropriations Committee’s top Democrat when Congress began funding Restore-L in late 2015.

The Restore-L mission was initially expected to cost between $626 million and $753 million, with a potential launch window of the second half of 2020, according to NASA. That did not occur, as the mission kept running into delays and rising costs. The most current OSAM-1 public timetable indicated a 2026 launch date.

NASA officially released a budget for OSAM-1 in 2020, following the Restore-L mission’s redesign. NASA estimated that the cost of design, construction, launch, and operation would be $1.78 billion at the time. According to Jimi Russell, a NASA spokesperson, an independent review board NASA formed last year to look into the OSAM-1 mission assessed the project’s potential overall cost might reach $2.35 billion.

Since 2016, the satellite servicing market’s actual conditions have also evolved. Many businesses are developing commercial satellite maintenance solutions, and as OSAM-1 would have shown with the Landsat 7 Earth-imaging satellite, the satellite industry has moved away from refilling unprepared spacecraft.

Rather, businesses are concentrating more on finding alternative ways to prolong satellite life. The Mission Extension Vehicle, created by Northrop Grumman, is able to navigate by latching onto a satellite without requiring the customer spacecraft to make any cuts in order to refuel. Some businesses are considering satellites that have refueling ports built right in. In order to provide its satellites with regular servicing and the capacity to maneuver and burn propellant without worrying about running out of fuel, the US military wants to station fuel depots and tankers in space.

For the OSAM-1 mission, Maxar is the primary contractor for NASA and is in responsibility of providing the robotic assembly payload in addition to the spacecraft platform. NASA said that the “broader community evolution away from refueling unprepared spacecraft” has “led to a lack of a committed partner” on the mission in a statement announcing the decision to abandon OSAM-1.

A guiding premise of NASA’s OSAM-1 project was to develop and validate satellite servicing technologies before transferring them to the private sector for application in the marketplace. However, many of the features that OSAM-1 would have been able to display were no longer attractive to the commercial sector.

“Technologies developed as part of OSAM-1 have been previously made available for commercial licensing and will continue to be available, albeit with no additional technology maturation or flight demonstration,” Russell said in a statement.

After NASA notified Congress as per protocol, it will “complete an orderly shutdown, including the disposition of sensitive hardware, pursuing potential partnerships or alternative hardware uses, and licensing of applicable technological developments.” NASA said that this is how it intends to proceed.

The primary OSAM-1 spacecraft was transported by Maxar last year from its Californian manufacturer to the Goddard Space Flight Center, where teams were tasked with installing robotic arms and the modular Ka-band antenna that the mission was supposed to assemble in orbit. However, the inspector general of NASA claims that this milestone was accomplished 2.5 years later than expected.

A significant portion of the OSAM-1 mission’s cost escalation and delays, according to NASA’s inspector general’s assessment, “can be traced to Maxar’s poor performance” on the spacecraft and SPIDER contracts.

“In our discussions with Maxar officials, they acknowledged that they were no longer profiting from their work on OSAM-1,” the inspector general reported. “Moreover, project officials stated that OSAM-1 does not appear to be a high priority for Maxar in terms of the quality of its staffing.”

The inspector general claimed that NASA was unable to provide Maxar with incentives to enhance its performance because of the terms of the company’s hard fixed price contracts with the space agency. NASA gave Maxar labor worth about $2 million in 2022 and 2023 to help with systems engineering and flight software.

One of OSAM-1’s robotic arms and a stowage platform—which would secure the satellite’s contents before launch—were also delivered by Maxar to NASA last year. The last two robotic arms were expected to be delivered this year, according to a Maxar representative named Eric Glass.

“While we are disappointed by the decision to discontinue the program, we are committed to supporting NASA in pursuing potential new partnerships or alternative hardware uses as they complete the shutdown,” Glass said. “We look forward to future opportunities to partner with NASA on innovative and pioneering technologies.”

Maxar reported additional reasons for OSAM-1 delays in their answer to the inspector general’s report from the previous year. These reasons included the COVID-19 pandemic and issues with creating the NASA-led servicing payload that would actually refuel Landsat 7 in orbit. “Maxar Space Systems’ contracts represent only about 15 percent of the overall program budget,” the business stated.

NASA stated that it is investigating ways to lessen the effect of OSAM-1’s cancellation on Goddard employees. OSAM-1 is being worked on by about 450 contractors and NASA workers.

Topics #NASA #Project for Satellite Maintenance