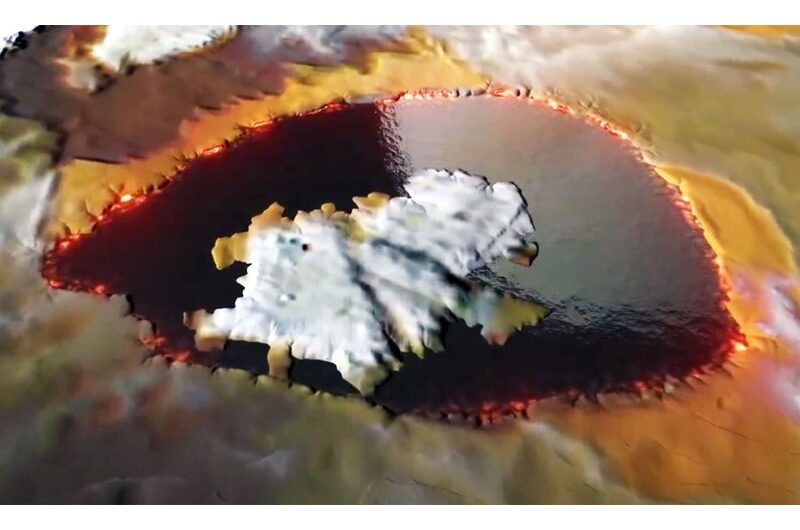

On Saturday, December 30, NASA’s Juno spacecraft will sail by Jupiter’s moon Io at its closest point in more than 20 years. The pass, which is approximately 930 miles (1,500 kilometers) away from the surface of the solar system’s most volcanic planet, is anticipated to enable Juno equipment to produce an abundance of data.

According to Scott Bolton, the principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, “the science team is studying how Io’s volcanoes vary by combining data from this flyby with our previous observations.” We’re interested in finding out how frequently they erupt, how hot and luminous they are, how the lava flow’s structure varies, and how Io’s activity relates to the movement of charged particles in Jupiter’s magnetosphere.

On February 3, 2024, Juno is slated to do another extremely close flyby of Io, this time coming within approximately 930 miles (1,500 kilometers) of the planet’s surface.

In addition to providing the first views of the moon’s north and south poles, the spacecraft has been tracking Io’s volcanic activity from a distance of approximately 6,830 miles (11,000 kilometers) to over 62,100 miles (100,000 kilometers). Additionally, the spacecraft has conducted close flybys of Ganymede and Europa, Jupiter’s icy moons.

According to Bolton, “Juno will explore the origin of Io’s intense volcanic activity, whether a magma ocean exists beneath its crust, and the significance of tidal forces from Jupiter, which are relentlessly squeezing this tortured moon” with its two near flybys in December and February.

The solar-powered spacecraft, which is currently in the third year of an extended mission to examine Jupiter’s formation, will also investigate the ring system, which is home to some of the gas giant’s inner moons.

During the Io flyby, Juno’s three cameras will be in action. The heat signatures released by the volcanoes and calderas that blanket the moon’s surface will be gathered by the infrared Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM). The mission will provide the highest-resolution surface image to date using its Stellar Reference Unit, a navigational star camera that has also yielded important scientific data. Also, visible-light color photos will be captured by the JunoCam imager.

Originally intended to be used for up to eight flybys of Jupiter, JunoCam was installed aboard the spacecraft for public participation. Juno’s 57th orbit around Jupiter, where the spacecraft and cameras have survived one of the harshest radiation environments in the solar system, will include the forthcoming flyby of Io.

“Over the last few orbits, the cumulative effects of all that radiation have begun to show on JunoCam,” stated Ed Hirst, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California, project manager for Juno. Images from the most recent flyby reveal a decrease in the dynamic range of the imager as well as the emergence of “striping” noise. Our engineering team has been developing ways to minimize radiation damage and maintain the imager’s functionality.

The Juno team modified the spacecraft’s intended future trajectory to include seven additional far-off Io flybys (for a total of 18) in the extended mission plan following several months of research and evaluation. Following the near encounter on February 3, the spacecraft will pass Io every other orbit, with the distance between each orbit increasing: The initial one will occur approximately 10,250 miles (16,500 kilometers) above Io, while the final one will occur approximately 71,450 miles (115,000 kilometers) above Io.

During the flyby on December 30, the spacecraft’s orbit around Jupiter will be shortened from 38 days to 35 days due to the gravitational attraction of Io. The flyby on February 3 will cause Juno’s orbit to decrease to 33 days.

After that, as a result of Juno’s altered trajectory, Jupiter will obscure the Sun from the spacecraft for roughly five minutes during perijove, or the moment when the orbiter is closest to the planet. The solar-powered spacecraft will experience darkness for the first time since its flyby of Earth in October 2013, but not for long enough to have an impact on how it functions as a whole. For the remainder of its extended mission, which concludes in late 2025, the spacecraft will witness solar eclipses like these during each near flyby of Jupiter, with the exception of the perijove on February 3.

The spacecraft will conduct a series of occultation tests beginning in April 2024 to investigate Jupiter’s upper atmospheric composition using Juno’s Gravity Science experiment. This information is crucial for understanding the planet’s shape and internal structure.

Additional Information About the Mission

The chief investigator of the Juno project, Scott J. Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, has the mission managed by JPL, a part of Caltech located in Pasadena, California. NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama oversees the agency’s New Frontiers Program on behalf of the Science Mission Directorate in Washington, D.C. Juno is a component of this program. The spacecraft is built and operated by Denver-based Lockheed Martin Space.

Topics #Juno #Jupiter's Angry Moon Io #NASA